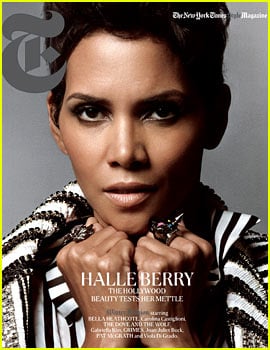

Halle Berry is

gorgeous

on the cover of

T, The New York Times Style Magazine‘s women’s fashion cover.

Here’s what the 46-year-old

Cloud Atlas actress had to share with the mag:

On keeping herself grounded: “I always felt like the underdog. Behind the eight ball. I learned not to be too high on the hog. Even that night I won the Oscar, I had a fundamental knowing, it was just a moment in time. Driving home that night, back to my house, I felt like Cinderella. I said, ‘When this night is over, I’m going back to who I was.’ And I did.”

On perceiving her image growing up: “My mother helped me identify myself the way the world would identify me. Bloodlines didn’t matter as much as how I would be perceived” — as

beautiful

but also as a black woman in a world in which the images of beautiful, successful black women were notably absent.”

Tom Hanks, on Halle’s acting ability: “She’s got this way of looking at the camera. Very deep and still. There’s a calm about her, and that comes through in her performances. She’s a peaceful pond on a late summer’s day. No maintenance or hurly-burly.”

For more from

Halle, visit

tmagazine.com!

Photograph by Cedric Buchet. Styled by Bill Mullen. Fashion assistants: Mauricio Quezada and Mollie Maguire. Hair by Neeko at Dew Beauty Agency and Salon Sessions using Oribe. Makeup by Kara Yoshimoto Bua for Chanel using Revlon. Manicure by Deborah Lippmann.Halle Berry models every season’s wardrobe essentials: a great jacket and classic denim. Salvatore Ferragamo jacket, $17,300; (800) 628-8916. Isabel Marant shirt, $145; (212) 219-2284. Hermès belt, $2,050; hermes.com. Guess jeans, $98; guess.com. Janis by Janis Savitt necklace, $588, bracelets, $625 and $940, and rings, $125, $150 and $200; (212) 245-7396.

Photograph by Cedric Buchet. Styled by Bill Mullen. Fashion assistants: Mauricio Quezada and Mollie Maguire. Hair by Neeko at Dew Beauty Agency and Salon Sessions using Oribe. Makeup by Kara Yoshimoto Bua for Chanel using Revlon. Manicure by Deborah Lippmann.Halle Berry models every season’s wardrobe essentials: a great jacket and classic denim. Salvatore Ferragamo jacket, $17,300; (800) 628-8916. Isabel Marant shirt, $145; (212) 219-2284. Hermès belt, $2,050; hermes.com. Guess jeans, $98; guess.com. Janis by Janis Savitt necklace, $588, bracelets, $625 and $940, and rings, $125, $150 and $200; (212) 245-7396.

It’s 10 in the morning, and already Halle Berry is being chased, though a better word for what’s going on might be “hunted.” Considering this, the Oscar-winning actress — one of the stars of the film “

Cloud Atlas” — makes her way into the lounge of the Four Seasons Hotel as if emerging from savasana at the end of a two-hour yoga class. Her smile appears warm, her outfit (perfectly ripped jeans and a T-shirt) unremarkable. Her hair — back to the short cut she has favored over the years, that only a woman this beautiful could pull off with such success — looks great though un-fussed-over, as does the rest of her, never mind that she just celebrated her 46th birthday. She doesn’t carry herself like a woman under siege.

“They’re outside my house every morning,” she says. We’re speaking of the paparazzi, of course. Even here in L.A. — a town not short on movie stars — Halle Berry gets special attention from the press. Not the good kind.

“I get it about the celebrity stuff,” she tells me softly, sliding into her seat. “It’s part of my job to recognize that there’s a certain part of my life the public wants to hear about. But it’s not O.K. that they’re doing terrible things to my daughter. One night, after they chased us, it took me two hours just to get her calmed down enough to get to sleep.”

Nahla (the name means “gift” in Swahili and “drink of water” in Arabic) is 4, the child of Berry’s five-year relationship with Gabriel Aubry, a French-Canadian model 10 years her junior, from whom she parted (cordially, at first, with vows on both sides of working together as parents, for the good of their child) two and a half years ago. Somewhere along the line, the plan broke down. During the Cape Town filming of “Dark Tide” in 2010, Berry (already separated from Aubry, to whom she was never married) got together with her French co-star, Olivier Martinez, to whom she is now engaged. In June she was ordered to pay Aubry $20,000 a month in child support. Nobody’s pretending they’re friends anymore.

Berry’s petition for a custody arrangement that would allow her to move to France is currently in the courts, with accusations flying from both sides and experts testifying that the parents should work things out. Meanwhile, the men with cameras stake out Berry’s house every morning and follow her wherever she goes. Including here.

She and Nahla are just back from the Toronto Film Festival, site of the “Cloud Atlas” premiere, where she saw the film for the first time. Some reviewers compared “Cloud Atlas” to Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” called it revolutionary, an artistic masterpiece. Other critics displayed considerably less awe — including one from The Times, who used the word “dopey.”

In any case, Berry’s role in the movie will surely be termed a comeback. After winning an Oscar for “Monster’s Ball” in 2002, she continued to work almost nonstop until her daughter’s birth in 2008, at age 41, then took two years off. She has made a couple of movies since then, but with “Cloud Atlas” it feels very much as if Berry is back — even if the actress herself doesn’t see it that way. “I never went anywhere,” she says. “I just seized the chance to be in an extraordinary film with an extraordinary cast, exploring an idea that’s relevant to everyone.”

It is without question her most ambitious role in years. In the film, directed by Andy and Lana Wachowski, who made “The Matrix,” and Tom Tykwer, Berry plays six characters, among them: a 19th-century Maori tribeswoman enslaved on a tobacco plantation; the sexually frustrated wife of a maniacal 1930s German composer; an investigative journalist in 1970s San Francisco, attempting to avert a nuclear-plant disaster; and an otherworldly refugee from a dying tribe in the future on a doomed planet. For that role, Berry needed not simply to look good in a white jumpsuit (she did) but also to speak in an invented dialect with her co-star Tom Hanks. And she had to age around 50 years, believably, with her beauty and sexuality intact.

“She’s got this way of looking at the camera,” Hanks says. “Very deep and still. There’s a calm about her, and that comes through in her performances. She’s a peaceful pond on a late summer’s day. No maintenance or hurly-burly.”

No hurly-burly. Except in her private life: a domestic violence episode that left her with an 80 percent hearing loss in one ear. Hit-and-run charges from an accident in 2000. A four-year marriage to the baseball player David Justice, resulting in a breakup that Berry has described as having precipitated thoughts of suicide.

Her second marriage, to the singer Eric Benét, ended after Benét admitted infidelities and checked into rehab for that old Hollywood standby, sex addiction.

Last year, a stalker trespassed on Berry’s property three times over the course of as many days. After serving six months in prison, he was ordered to undergo psychiatric treatment and issued a restraining order.

Now comes the custody struggle with Gabriel Aubry. And, despite her vow, delivered emphatically on Oprah’s couch, in 2004, that she would “never marry again — never,” she is engaged to yet another fabulously handsome performer.

I have to ask the question: “Why have you made such bad choices in men?”

“My picker’s broken,” she says with a laugh. “God just wanted to mix up my life. Maybe he was thinking, ‘This girl can’t get everything! I’m going to give her a broken picker.’ ” She says it’s fixed now.

Berry’s looks are no doubt a great gift. Even now, more than halfway through her 40s, she retains perfect skin, a long, elegant neck and a body that is both slim and womanly. (She says a diagnosis of Type-1 diabetes, at age 19, made healthy eating and exercise a necessity.) But, she says, “just because they see my face doesn’t mean they see me. A person’s self-esteem has nothing to do with how she looks.

“If it’s true that I’m beautiful,” she adds, “I’m proof of that. Self-esteem comes from who you have in your life. How you were raised. What you struggled with as a child.”

Berry grew up in Cleveland as the child of a white mother (a psychiatric nurse) and a black, alcoholic father — a hospital orderly — who abused her mother and older sister (not Berry herself, she says), and who left when she was 4. He returned six years later for what she describes as “the worst year of my life.” But it was her mother, Judith, who raised her.

After her mother showed up for the first time at her all-black elementary school, Berry was shunned. “Kids said I was adopted,” she says. “Overnight, I didn’t fit in anymore.” When the family moved to the suburbs in search of a better education for Berry and her sister, she was suddenly the lone black child in a nearly all-white school. People left Oreo cookies in her locker. When she was elected prom queen, the school principal accused her of stuffing the ballot box and suggested she and the white runner-up flip a coin to see who got to be queen. Berry won the toss.

“I always had to prove myself through my actions,” she says. “Be a cheerleader. Be class president. Be the editor of the newspaper. It gave me a way to show who I was without being angry or violent. By the time I left school, I had a lot of tenacity. I’d turned things around.”

When she was 16, her mother stood with her in front of a mirror and asked what she saw. “My mother helped me identify myself the way the world would identify me,” Berry says. “Bloodlines didn’t matter as much as how I would be perceived” — as beautiful but also as a black woman in a world in which the images of beautiful, successful black women were notably absent.

In the late 1960s, when Berry was a toddler, it wasn’t hard to find a black maid on the screen, large or small. But except for Diahann Carroll, and Nichelle Nichols on “Star Trek,” there were virtually no glamorous black leading ladies on television. Before that, on the large screen there had been Dorothy Dandridge, a serious actress and singer, but one who never came close to achieving the fame or success of her white contemporaries Grace Kelly and Marilyn Monroe. Among Oscar winners, the only name on the list: Hattie McDaniel, for her role as the maid in “Gone With the Wind.” (And in 1990, Whoopi Goldberg, as Best Supporting Actress in “Ghost.”)

A similar problem faced her at home. “My mother tried hard,” Berry says. “But there was no substitute for having a black woman I could identify with, who could teach me about being black.”

A black school counselor named Yvonne Sims entered her life in fifth grade. She remains one of Berry’s closest friends. “Yvonne taught me not to let the criticism affect me. She inspired me to be the best and gave me a model of a great black woman.”

The model of a good man was harder to come by. Her mother had a boyfriend by this point — “a black man, which was important, and he was kind to us.” But the man who’d been the most central in shaping her picture of men remained her father. For a while there, she didn’t even know if he was dead or alive. (He died in 2003.)

After winning the Miss Teen Ohio contest, and later going on to become the first runner-up in the Miss U.S.A. pageant, Berry studied for a year at Second City in Chicago. While she was there she got a call from a manager in New York, Vincent Cirrincione, looking for a black actress to read for a soap opera. Knowing no one in New York but Cirrincione, she got on a plane. Her breakthrough came with a TV series called “Living Dolls,” which took her to Los Angeles, followed by Spike Lee’s “Jungle Fever” in 1991, in which she played a crack addict. She had intended to read for another role but told the director she wanted to play the drug addict. She remembers that Lee said, “Well, you better go wash off your makeup.” She did and she got the part.

Since then Berry has starred in more than 30 movies, winning, in addition to the first Academy Award for Best Actress ever given to a black woman, an Emmy for HBO’s “Introducing Dorothy Dandridge” in 2000. The scene in “Monster’s Ball” in which Berry’s character makes love to Billy Bob Thornton, playing a corrections officer who presided over her husband’s execution, stands as one of the most erotic I’ve ever seen on the screen, as a naked and moaning Halle Berry — more visibly naked than most A-list actresses would allow — crawls over Thornton’s character growling words that will no doubt be associated with the actress forever: “Make me feel good.”

She also appeared in “X-Men” and played a Bond Girl and Catwoman, for which she won a Razzie award for Worst Actress. She actually showed up to accept, delivering, at the podium, a perfect satirical portrayal of a weeping and trembling actress, gripping her award tightly, thanking every person she ever met.

Though Berry seems reluctant to speak of racism in her profession, it’s plain, talking with her, that she’s not unacquainted with its effects — having been told, over the years, that she was alternately too black or not black enough. The 1993 movie “Father Hood” may not have been great, but it is distinguished in Berry’s résumé as the first instance of a film role she won that had not been specifically designed for a black actress.

Berry identifies herself as African-American, and in her acceptance speech for the Oscar, she chose to honor Dorothy Dandridge, Lena Horne and Diahann Carroll. Yet spending time with Berry, I have the feeling that more than belonging to one race or another, what she feels like most is an outsider.

We speak of her own experience, but also that of President Obama. She hasn’t met him, but she attended the inauguration and feels a connection to another dark-skinned child of an absent black father, raised by a white mother. “Being biracial is sort of like being in a secret society,” she says. “Most people I know of that mix have a real ability to be in a room with anyone, black or white.”

“I come from humble beginnings,” she says. “I always felt like the underdog. Behind the eight ball. I learned not to be too high on the hog. Even that night I won the Oscar, I had a fundamental knowing, it was just a moment in time. Driving home that night, back to my house, I felt like Cinderella. I said, ‘When this night is over, I’m going back to who I was.’ And I did.”

In “Cloud Atlas,” the range of characters Berry portrays goes from the most humble to a woman of the future, Meronym, whom Berry describes as “the priestess of the world.” These characters are meant to represent aspects of the same soul, reincarnated over time in different bodies and at different stages of its evolution. If this is how a human soul evolves, I ask her, where has hers gotten to so far?

“I’ve been all those women,” she tells me. “Luisa Rey” — the crusading journalist reporting on the cover-up of an imminent nuclear disaster — “corresponds to who I was when I first started to make a living, the part of myself that was hopeful, the part that believed I could do anything. Meronym is that part of me I discovered after I had Nahla. I know more than my daughter does. And it’s my job to lead her through the world and find a safe place for her. Even though I know I’ve made mistakes, myself.”

Before we met, I had heard Berry described as “fragile.” Something about her suggests that the gifts of beauty, talent and magnetism are not necessarily sufficient to ensure a person’s emotional well-being. During her Oprah interview, her voice broke more than once on the subject of having lost her trust in men, and though that was eight years ago, the evidence of vulnerability remains a significant part of what draws you to Halle Berry. She is a woman whom people (men, in particular) would doubtless feel moved to protect. Though it is possible that those same men may end up being the ones from whom she needs protection.

But as much as some women may possess a fragile center beneath a tough exterior, it seems to me that for Berry the opposite applies. My first impression was her soft voice, gentle manner, accessibility and warmth — what Tom Hanks describes as “a Zen-like peacefulness.” Yet there’s a steely toughness in her core, without which she would probably not have gotten where she has.

During the first week of filming “Cloud Atlas,” Berry broke her foot in Majorca. “She called it ‘a bump in the road,’ ” Hanks says. “But this was a severe break. In between takes, she had to be helped to her chair because she couldn’t stand up on her own.”

In an e-mail to me, Andy and Lana Wachowski wrote, “The first day after she got her cast off her foot she had to do a scene standing on a rock in the middle of a river.” Berry slipped on her broken foot, and the entire crew screamed with her — it was obviously terribly painful. Then, they recalled, “this fire just ignited in her eyes and she was suddenly Meronym again. The take was flawless. It’s the one in the film. She is one of the gutsiest actors we’ve ever worked with.”

We are on our third cup of tea when a concierge at the Four Seasons approaches Berry with a note. A substantial crowd of photographers has now gathered outside. Her expression, seeing this, appears resigned. It is not a remotely unfamiliar event but one that will require her to be hustled out a back exit of the hotel. Hanks, describing what Berry and Nahla experience, calls it a “nearly criminal level of persecution,” uniquely reserved for female stars and their children. Halle Berry more than almost any of them.

After completing work on “Cloud Atlas,” Berry had been scheduled to make her Broadway debut opposite Samuel L. Jackson in “The Mountaintop,” Katori Hall’s two-person play about Martin Luther King Jr.’s final hours. She stepped away from the production last year as a result of “child-custody issues.” Currently Nahla spends alternate weekends with her father while Berry pursues her custody petition — a choice she says has as much to do with French regulations prohibiting the press from pursuing children as it does with the nationality of the man she plans to marry.

“I can’t grow my daughter in L.A.,” she tells me. “You take a little child who is just trying to learn about the world and have all these people with cameras chasing after her, calling things out to her about her mother. It’s starting to make her feel special and different. I want her to feel special and different, but not for the reason of being my child.”

I ask Berry what she’d do — where she’d go — if she could manage to evade the press, and not look like Halle Berry, for just one day.

“I’d go to the market with my daughter,” she says. “Go to Santa Monica Pier and take her on a ride. Nothing special. Just live some normal life for once.”

Her favorite book to read to Nahla, she says, is “Harold and the Purple Crayon,” in which a 4-year-old boy, wanting to go for a walk but finding no moon to light his way, takes out his magic crayon and draws one, along with a path to walk on and a series of places that lead him to other adventures, and finally back home.

“It’s a book about creating your own reality,” Berry says. “Sometimes, with Nahla, we’ll take out the crayons and I’ll say, ‘If you could be Harold — only you’re Nahla — and you had that purple crayon, where would you go?’

“We think up all kinds of things to do and places to go,” she says. Could be Santa Monica. Could be Paris. “One thing about Harold, he’s colorless. That crayon can take you anywhere.”

Halle Berry models every season’s wardrobe essentials: a great jacket and classic denim. Salvatore Ferragamo jacket, $17,300; (800) 628-8916. Isabel Marant shirt, $145; (212) 219-2284. Hermès belt, $2,050;hermes.com. Guess jeans, $98; guess.com. Janis by Janis Savitt necklace, $588, bracelets, $625 and $940, and rings, $125, $150 and $200; (212) 245-7396.

Halle Berry models every season’s wardrobe essentials: a great jacket and classic denim. Salvatore Ferragamo jacket, $17,300; (800) 628-8916. Isabel Marant shirt, $145; (212) 219-2284. Hermès belt, $2,050;hermes.com. Guess jeans, $98; guess.com. Janis by Janis Savitt necklace, $588, bracelets, $625 and $940, and rings, $125, $150 and $200; (212) 245-7396.

Versace jacket, $4,525, and shirt, $1,075; (888) 721-7219. Hudson jeans, $198; hudsonjeans.com.

Versace jacket, $4,525, and shirt, $1,075; (888) 721-7219. Hudson jeans, $198; hudsonjeans.com.

Chanel jacket, $10,067; (800) 550-0005. Graff necklace and rings, price on request; graffdiamonds.com.

Chanel jacket, $10,067; (800) 550-0005. Graff necklace and rings, price on request; graffdiamonds.com.

Mugler jacket, price on request; mugler.com. Burberry Prorsum shirt, $1,295; burberry.com. 7 For All Mankind jeans, $215;7forallmankind.com. Christian Louboutin shoes, $625;christianlouboutin.com. Mawi bracelets, $600, $835, $1,020, and ring, $400.

Mugler jacket, price on request; mugler.com. Burberry Prorsum shirt, $1,295; burberry.com. 7 For All Mankind jeans, $215;7forallmankind.com. Christian Louboutin shoes, $625;christianlouboutin.com. Mawi bracelets, $600, $835, $1,020, and ring, $400.

Lanvin jacket, $10,595, and necklaces, $795 and $895;bergdorfgoodman.com. Isabel Marant shirt, $225. J. Brand jeans, $196; jbrandjeans.com. Max Mara hat, $395; (212) 879-6100. Eddie Borgo necklace, $875; eddieborgo.com. Eddie Borgo cuff bracelet, $450; neimanmarcus.com. Eddie Borgo cone bracelet, $525;bergdorfgoodman.com. Noir Jewelry bracelet, $110;noirjewelry.com. Fashion assistants: Mauricio Quezada and Mollie Maguire. Hair by Neeko at Dew Beauty Agency and Salon Sessions using Oribe. Makeup by Kara Yoshimoto Bua for Chanel using Revlon. Manicure by Deborah Lippmann.

Lanvin jacket, $10,595, and necklaces, $795 and $895;bergdorfgoodman.com. Isabel Marant shirt, $225. J. Brand jeans, $196; jbrandjeans.com. Max Mara hat, $395; (212) 879-6100. Eddie Borgo necklace, $875; eddieborgo.com. Eddie Borgo cuff bracelet, $450; neimanmarcus.com. Eddie Borgo cone bracelet, $525;bergdorfgoodman.com. Noir Jewelry bracelet, $110;noirjewelry.com. Fashion assistants: Mauricio Quezada and Mollie Maguire. Hair by Neeko at Dew Beauty Agency and Salon Sessions using Oribe. Makeup by Kara Yoshimoto Bua for Chanel using Revlon. Manicure by Deborah Lippmann.