Exploring DID on the Big Screen

In Frankie & Alice, Halle Berry Portrays Mental Illness with Compassion and Perseverance

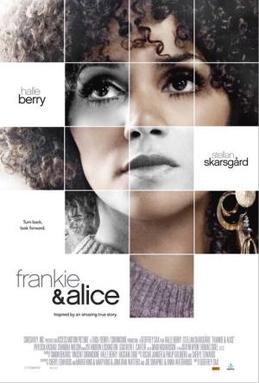

By Katrina Gay, National Director of Communications, and Courtney Reyers, Director of Publishing, NAMIIn her latest film, Frankie & Alice, Academy Award-winner Halle Berry plays a ’70s-era go-go dancer with dissociative identity disorder (DID) named Frankie—a black woman with two alternative identities: a scared, 7-year-old little girl named Genius and a white, bigoted Southern belle named Alice. With the care and support of a dedicated psychiatrist, Frankie is able to progress on a recovery journey that saves her and helps her reclaim her life.

The film is set to premiere in select theaters on April 4, 2014. NAMI recently talked with Ms. Berry about her role, the film and her commitment to the project.

Why was this project important to you?

Aside from the role being desirable as an actor—the opportunity to embrace a challenging, complex role—it was important to me because the film helps put light into a dark space. People who live with mental illness often struggle. Others often look down on them or have negative opinions of them. Hopefully, this film will do some good. I am happy that the film is being released in theaters and, eventually, DVD, and hope that it promotes the importance of compassion for others, that it helps to educate the public. In playing Frankie Murdoch, based on the true story of her life, as I grew to understand the condition of DID, and as I acted through Frankie’s struggle, I grew as a human being. I would like to inspire that with this film.

You play a character that lives with DID. How did you prepare for this role?

Initially, it was through meeting the real woman that the story is modeled after, Frankie. She was my greatest source of information and inspiration; I wanted to protect her and her story. I wanted to understand and portray her stories of frustration and fear. I felt responsible for making sure that these stories were addressed in the movie. I also did basic reading on DID and mental illness—but most of my understanding and inspiration came from Frankie’s life and her story; the personal story is the best source. And finally, Dr. Oz, her doctor, had transcripts as well that spoke to his feelings. I was able to secure some videotapes of health care providers who have worked with and helped people with DID in their recovery. Watching these was very beneficial to helping me ensure that we were incorporating the medical side of the condition into the film, too.

When I recently watched the film, I have to say that parts of the film were difficult for me to watch. Witnessing the scenes where Frankie was self-destructive was hard to see—and yet I couldn’t look away. It was very real. What do you want people to take away from the film, and why was it important for you to include these raw moments?

Often, movies are sheer entertainment. This movie was, of course, intended to be entertaining, but it was also designed to help educate and make people aware. We wanted to offer a human perspective to mental illness, to reveal the constant life struggle of mental illness and the devastating impact it can have. I hope that people are enlightened as a result of Frankie & Alice, that they learn something. I want people to feel hopeful. Watching the character come to terms with what her illness was and her process and acceptance of that—it was hopeful. Frankie manages to find her journey of recovery, to live her life and to eventually achieve a full life. She will always struggle with her condition, to some degree, for the rest of her life because it is a part of who she is, but she has learned how to deal with it. The end message, therefore, is positive and uplifting. And part of it is this: When we can embrace recovery, there is hope.

Did playing this role change you at all? Did it change the way you see mental illness or your understanding of what individuals dealing with mental illness are going through?

Yes, it did. Speaking to Frankie when I was preparing for this role—listening to what she told me—I came to understand that there were moments that she felt like she didn’t want to be here anymore. This illness had a hold on her; it was so big and large. But underneath it, a deep desire and a true love of self won. This battle within and a realization of her own love and desires to accomplish her dreams helped her to keep fighting. Yes, to keep fighting. And Dr. Oz, her psychiatrist, made her feel worthy. He validated her and reminded her of that character genius in her that was there. Her relationship with her psychiatrist was, for Frankie, instrumental in helping her hold on to keep fighting to manage her condition.

As we discussed at the beginning of this conversation, NAMI is the largest grassroots organization in the country, and we work every day to make sure people living with mental illness get the services and support they need. What do you want other people to know? If you had one thing to say to NAMI members, what would it be?

That we are all worth it. What I found in preparing for this role was that, sadly, most people don’t think they are worth it. They don’t have strong support systems that remind them that they are worth it. Loving families are a huge help—but not everyone has access to a loving and supportive family. So, if they don’t, they need to know that help and support are important and that they are available. We have to help people and assist them in holding on and finding ways to get the support they need.

Throughout your career, have you seen a connection between creativity and mental illness?

I have been curious about that myself, yes. Over the years, I have looked into it. Yes. There is an argument to be made—some say yes, and some say no—that there is a connection between creativity and mental illness, at least in the entertainment industry. It is really hard to say one way or the other, but within my industry, I have come across some of the most complicated individuals who are highly creative who have on some level suffered from some sort of mental illness. There are many things about them that would lend you to believe they have a mental health condition that has impacted their lives and, thus, their creativity. I do believe that as a matter of point, if you have a mental illness you may not be creative and, conversely, if you are creative you may not have a mental illness. But there does often seem to be some connection.

NAMI has a large membership and community. Are there any parting thoughts you’d like to share with them?

My main message is one of hope. As in the movie, the way the movie ends, Frankie found a way to rise above her illness. There were moments when it could have destroyed her life and her will. But in the end, her will to live and survive ultimately won. This is a message for all of us, regardless of our personal struggle, but certainly one that is important for people affected by mental illness. I worked on this for eight years. It has been my passion to bring this to light. I was influenced by my mother, who for 35 years was a psychiatric nurse in the VA. In addition, I have had mental illness and alcohol abuse in my family, and I think that many other people can say the same thing. The stories of mental illness have been a part of my life and have been on my radar for a long time. When the story of Frankie Murdoch came along, it was no surprise to those who know me that I would champion this film. Now, that fight continues: I have worked equally hard so that the film is distributed, is available and gets seen. Finally, the film is coming out! And these important messages—fighting for self, human compassion, hope, understanding—will become part of others’ awareness, too.

Halle Berry is an actress, producer, Revlon cosmetics spokesperson and former model. She is the mother of two children, a daughter and son, and the wife of French actor Olivier Martinez. She was the first and, as of 2013, only woman of African-American descent to win an Oscar for Best Actress, receiving the Academy Award® in 2002 for her performance in Monster’s Ball. In addition to Frankie & Alice, Ms. Berry can be seen in the Steven Spielberg futuristic thriller series, “Extant,” which debuts on the CBS network Wednesday, July 2. NAMI is grateful to Codeblack Films, Lionsgate and Halle Berry for their support of our important movement. For more information, including theater and ticket information, a discussion guide, resources and more, visit NAMI.org/Frankie&Alice, or follow the conversation at #FrankieAndAlice.

About Dissociative Identity Disorder

Dissociative Identity Disorder (DID) is a dissociative disorder involving a disturbance of identity in which two or more separate and distinct personality states (or identities) control the individual’s behavior at different times. When under the control of one identity, the person is usually unable to remember some of the events that occurred while other personalities were in control. The different identities, referred to as “alters,” may exhibit differences in speech, mannerisms, attitudes, thoughts and gender orientation. The alters may even differ in “physical” properties such as allergies, right- or lefthandedness, or the need for eyeglass prescriptions. These differences between alters are often quite striking.“DID—once called multiple personality disorder—is frequently the result of severe stress in early life—often incest or multiple rape cases—and functions as a coping mechanism for the person,” says Dr. William Lawson, professor and chairman at the Department of Psychiatry at Howard University in Washington, D.C. “It’s a serious mental disorder that occurs across all ethnic groups and all income levels, and has a high rate of self-harm and suicidality.” A person with DID may have as few as two alters or as many as 100; most people living with DID average about 10 different identities. Alters are often stable over time, continuing to play specific roles in the person’s life for years. Some alters may harbor aggressive tendencies that are directed toward individuals in the person’s environment or toward other alters within the person.

When a person with DID first seeks professional help, he or she is usually not aware of the condition. A very common complaint in people with DID is episodes of amnesia, or time loss. These individuals may be unable to remember events in all or part of a proceeding time period. They may repeatedly encounter unfamiliar people who claim to know them, find themselves somewhere without knowing how they got there or find items among their possessions that they don’t remember purchasing.

DID affects women nine times more often than men. Approximately one-third of individuals complain of auditory or visual hallucinations—but it is crucial that DID not be confused with schizophrenia, as the two illnesses require very different treatment.

Treatment for DID consists primarily of psychotherapy with hypnosis. The therapist seeks to make contact with as many alters as possible and to understand their roles and functions in a person's life. In particular, the therapist seeks to form an effective relationship with any personalities that are responsible for violent or self-destructive behavior, and to curb this behavior. The therapist seeks to establish communication among the personality states and to find ones that have memories of traumatic events in the person’s past. The goal of the therapist is to enable the individual to achieve a breakdown of separate identities and their unification into a single identity.

No comments:

Post a Comment